A lawyer stood up to put Jesus to the test, saying, "Teacher, what shall I do to inherit eternal life?" He said to him, "What is written in the law? How do you read?" And he answered, "You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your strength, and with all your mind; and your neighbour as yourself."

- St. Luke 10:25-27

Although it is a parable being told by our Lord, everyone who heard His response to the young lawyer’s question, “Who is my neighbour,” knew exactly the stretch of road which Jesus was describing. The journey from Jerusalem to Jericho was on a narrow, rocky road. There were outcrops of rock and sudden turns, which made it a favourite place for thieves to hide. In the fifth century, St. Jerome tells us that it was called "The Bloody Way." Even in the 19th century it was still necessary to pay safety money to the local sheiks before one could travel on it. When Jesus told this story, He was telling about the kind of thing that was happening constantly on the Jerusalem to Jericho road.

And we look at the characters in the story:

There was the traveler, who must have been reckless and not very prudent. People seldom attempted the Jerusalem to Jericho road alone. There would be some safety in numbers, so they almost always travelled in convoys or caravans. This man, however, had set out by himself, so he really had no one but himself to blame for the predicament in which he found himself.

There was the temple priest, who hurried past. He knew full well that if anyone touched a dead man, he was unclean for seven days, according to Jewish law. He couldn’t be sure, but it looked to him as though the man was dead, so to touch him would mean losing his turn of duty in the Temple, and he didn’t want to take that risk.

The Levite was fairly worldly-wise. He knew that the bandits on this road were in the habit of using decoys. One of them would act as though he were wounded, and when some unsuspecting traveler stopped to help, the others would rush in and overpower him. He wasn’t going to fall for that trick.

Then there was the Samaritan. Given the feelings of the Jews towards the Samaritans – a race of people who claimed Jewish roots, but who were half-breeds and so deemed to be worse than Gentiles – there was no doubt in the minds of those hearing this parable that the real villain of the story had arrived.

But what a surprise! He was the only one prepared to help. He may have been a heretic and an enemy as far as the Jews were concerned, but the love of God was obviously in his heart.

So the young lawyer poses the question, “Who is my neighbour,” and Jesus asks him what is written in the law. And He expands it into a second question: "How do you read?" Why did Jesus ask it in that way?

Strict orthodox Jews wore round their wrists little leather boxes called phylacteries, which contained certain passages of scripture, having to do with the love of God. “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, with all your mind, with all your strength.” So Jesus was saying to the scribe, "Look at the phylactery on your own wrist and it will answer your question." To that scripture, the scribes had added Leviticus 19:18, which teaches that a man should love his neighbour as himself. But this wasn’t enough for the strict Jew. With their absolute passion for defining things, the Rabbis tried to define who a man's neighbour was; and very often they confined the word “neighbour” to apply only to their fellow Jews. For instance, some of them said that it was illegal to help a Gentile woman at the time of childbirth, because that would only be bringing another Gentile into the world. So then, we can see that the scribe's question, "Who is my neighbour?" was a significant one.

So we have some important points here:

First, we must help a person, even when he has brought his trouble on himself, as this traveler had done.

Second, any person who is in need is our neighbour. Our help doesn’t stop with our own people, with our own kind. Our charity must be as wide as the love of God.

Third, the help we give must be practical and not consist only in feeling sorry. Compassion, to be real, has to show itself in deeds. This is part of what St. James means when he says: “faith without works is dead.”

And what Jesus said to the scribe, He says to us – “Go and do the same."

So we have some important points here:

First, we must help a person, even when he has brought his trouble on himself, as this traveler had done.

Second, any person who is in need is our neighbour. Our help doesn’t stop with our own people, with our own kind. Our charity must be as wide as the love of God.

Third, the help we give must be practical and not consist only in feeling sorry. Compassion, to be real, has to show itself in deeds. This is part of what St. James means when he says: “faith without works is dead.”

And what Jesus said to the scribe, He says to us – “Go and do the same."

________________________________

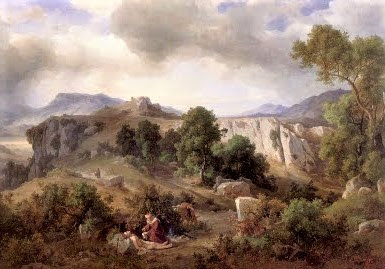

Painting: "Landscape In The Sabine Hills With The Good Samaritan"

by Friedrich Preller the Elder (1804-1878)